Nearly overtaking the fort itself, the Alamo’s continental sized mythos surrounds and infuses itself into the site as permanently as the stones in its walls. Today, the Alamo is as much a thing of legend as a physical place. Looking at the buildings in person or in a photo, I’m only able to vaguely make out the structure, my mind confused as the ingrained aura inflates the barracks, walls, and church to heroic proportions.

There are a handful of destinations like this spread across the US; places where the mythological shadow has overgrown the actual site. Often tucked into the corners of our country, these make up the skeleton supporting the American spirit, holding us up with the pillars born from our past and burning with the light of our past achievements.

Standing in the shadow of its fabled history, visiting the Alamo always seemed to me like an impossible feat. Writing it down as part of an itinerary for our first visit to San Antonio felt surreal, and, every time I looked at typed out, the trip took on the feeling of a pilgrimage, not simply a vacation.

Looking at The Alamo’s cream-colored outline on Google Maps, its placement in the middle of the city defied logic. As I turned right out of our hotel, I expected city blocks to appear out of nowhere and stretch my walk out into infinity, but before I ended the first song on my playlist – I was running my fingers along the Long Barrack wall.

When I finally stood in the Plaza, able see The Alamo all at once, I almost felt dizzy. My eyes were tracing the limestone roofline while my head was swimming in the mythic story – trying to stretch the small building into something that would loom with the weight of what had transpired here over one hundred and fifty years ago.

I was wrong about a lot of things to do with The Alamo, mainly my belief that I knew anything about The Alamo. For starters, as I looked across the plaza, I thought the building I saw was ‘The Alamo’ – which is like looking at a heart and thinking you see the entire person. In fact I didn’t even know it was a church before placing my hands upon its outer walls – so I guess I kind of always thought The Alamo was a fight at some frontier hacienda, not a Spanish Mission turned Texan Fort.

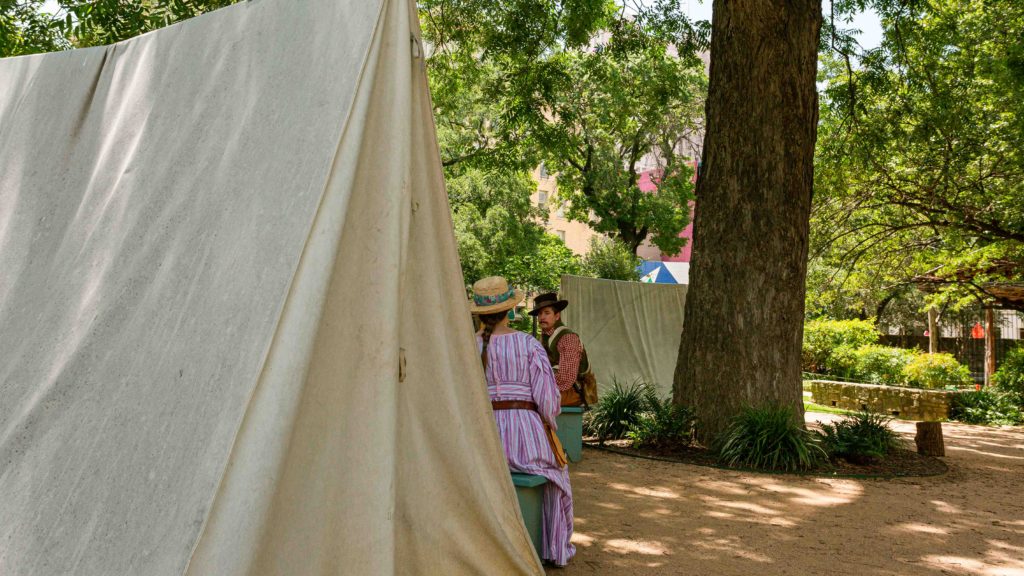

Augustine and Jade joined me in wandering around the grounds, stopping to talk to the period actors, see the fish, see all the fish, cross through the gardens, revisit the fish because we hadn’t see the ‘right one’. Then we made our way to the chapel, still considered a hallowed place.

Inside, the once-church-now-tomb is a size too small for a game of tag – unless you’re the person who’s it, and what felt nice and comfortable on a hot Texas summer day would have felt frigid and confining mid-winter 1723. It was sparsely furnished but people moved as if China dish covered tables were spread throughout the room. With the doors shut at each end, dust hung in the air with the stillness of late season ornaments despite the visitors making their way through the makeshift mausoleum.

Once outside, I stared back at the chapel like one might a cave painting in a sister language to their own. I had fused the mythological and the physical, but it was pulling apart again – possibly greater now that I had more details. The church was forever small now, but would always feel immense.

For the first time, I noticed the plaque set in the grass before the fort,

“our flag still waves proudly from the walls – I shall never surrender or retreat.”

The Alamo isn’t actually an American story. It is a Texan story. I think now that the fact that ‘The Alamo’ has a distinctly US feel shows off one of the best sides of the US – the potential for Americans to enfold the history, the heroes, the heart of others into our own story, and care so deeply about them that they become our own. With so much of US history defying this full-potential, finding it is truly special.